Enjoy this guest post by Melody Hobbs, Sarah Neessen, and Kathy Fitzgerald

Authors:

Melody Kay Hobbs, Ed.S. District Preschool Program Director and Classroom Teacher, Lenoir City Schools

Sarah Neessen, B.S. Classroom Teacher, Knox County Head Start

Kathy Fitzgerald, Ph.D. Assistant Clinical Professor, UTK Child and Family Studies

Growing Children’s Minds

Did you know….“when children engage in mature pretend play with their peers, they practice representational thinking, the same type of thinking needed for early literacy. In pretend play, children act out sophisticated narratives. Children use a combination of objects, actions, and language together in narrative sequences and use language outside of their daily vocabulary as they meaningfully act out different perspectives and roles” (Early Childhood Learning Knowledge Center, 2006, p.2).

Did you know….“when children engage in mature pretend play with their peers, they practice representational thinking, the same type of thinking needed for early literacy. In pretend play, children act out sophisticated narratives. Children use a combination of objects, actions, and language together in narrative sequences and use language outside of their daily vocabulary as they meaningfully act out different perspectives and roles” (Early Childhood Learning Knowledge Center, 2006, p.2).

Pretend play – what are we talking about?

Many might agree that play is important in the lives of young children. Interestingly, not all play is alike. Sarah Smilansky (1922 – 2006), an Israeli researcher, spent time studying children’s play alongside Piaget. Smilansky’s own research extended her work with Piaget, as she continued a focus on the correlation between children’s play and learning. In her book, Facilitating Play: A Medium for Promoting Cognitive, Socio-Emotional, and Academic Development in Young Children (1990), Smilansky and Shefatya identify four types of play:

- Functional Play (manipulation of toys),

- Constructive Play (building and making things),

- Games with Rules (starts around age 6 as children come to know games through the rules that define them), and

- Dramatic/Sociodramatic play (play in which a child engages as an actor, observer, and interactor). According to Smilansky and Shefatya (1990), sociodramatic [pretend] play is “a form of voluntary social play activity in which young children participate. It differs from other types of play in that it is person oriented and not material or object oriented” (p.3 & 21). It is in this type of play, sociodramatic pretend play, that children engage in highly complex thinking.

“In play a child is always above his average age, above his daily behavior; in play it is as though he were a head taller than himself.” Vygotsky, 1933/1967 (as cited in Bodrova & Leong, 2015, p.371)

Pretend play and mastery of mental tools

The work of Daniel El’konin (1904 – 1984) provides insight into the relationship between sociodramatic pretend play and children’s cognitive development. El’konin viewed sociodramatic play as the foremost activity influencing a preschool child’s mastery of ‘mental tools.’ According to El’konin, as children engage in mature pretend play they develop the mental capacity to master the tools of today as well as of tomorrow….”even those not yet invented” (Bodrova & Leong, 2015, p.377).

El’konin identified four distinct ways children exercise higher mental functions in mature pretend play (Bodrova & Leong, 2015):

- Pretend play affords opportunity for children to develop a sophisticated system of short and long term goals. At times, children must suspend the immediate goal of play to plan for the next scene. Take, for example, an ice cream shop scenario in which children must pause their role as customers in order to make paper money needed to purchase their ice cream.

- Pretend play fosters cognitive “decentering.” In sociodramatic play, children must ‘see’ from the perspectives of others. For instance, in the same play scenario described above, a child says “DING!” to ring a pretend bell alerting the ‘ice cream shop worker’ that she is ready to order. Understanding the perspective of the other child (a customer ringing the bell to order ice cream), the ‘ice cream shop worker’ responds, “What can I get for you today, ma’am?”

- Pretend play supports the development of mental representation. In pretend play, children must think about concepts that may or may not be concrete. In the ice cream shop scenario, the ‘mother’ states that she is buying chocolate ice cream for her child – even though there is no visible representation for the role of the daughter (such as a doll). This illustration underscores children’s use of abstract thinking and imagination during pretend play. Inasmuch as imagination is not a necessity for pretending, it is an end result.

- Pretend play supports intentionality in actions – both physical and mental. In sociodramatic play, children must follow the “rules of the role.” Referring again to the ice cream shop play scene, the ‘customers’ wait in line for the ‘ice cream shop worker’ to attend to each customer, resisting the desire to merely take what they want when they want it. Instead, the child’s role dictates how the child must communicate, respond, and navigate actions with others in role.

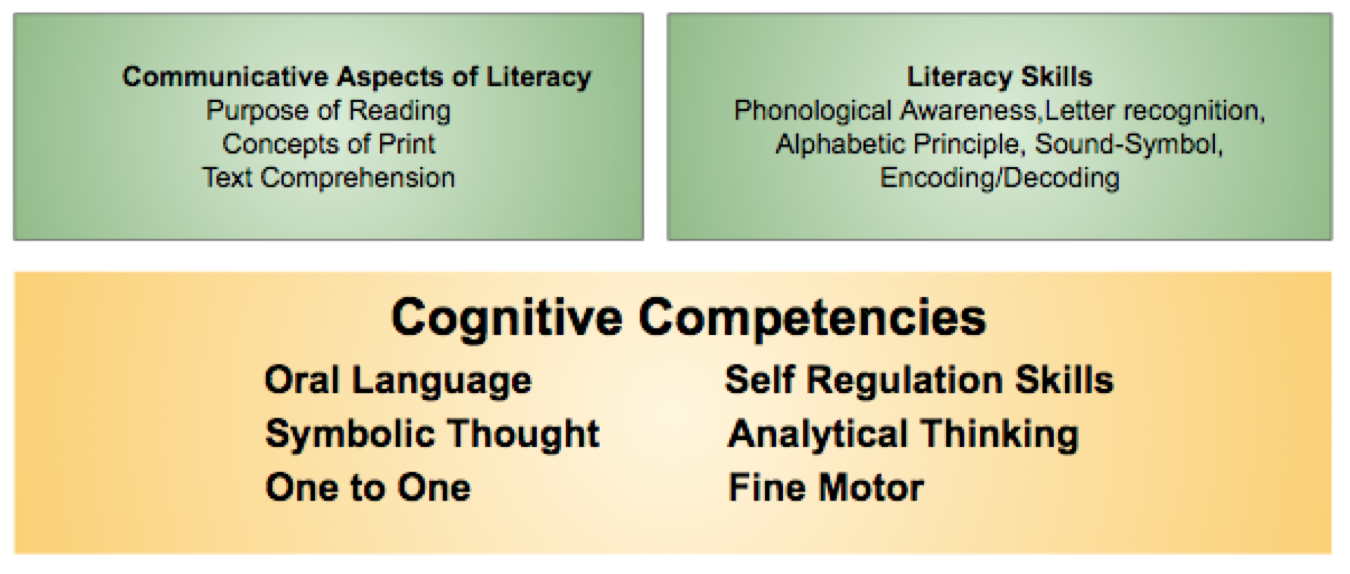

Pretend play: A vehicle for building cognitive competencies

*citation below

Our simplified interpretation of El’konin’s notion of mental tools provides a lens for conceptualizing how children’s engagement in sociodramatic play serves as a vehicle for developing cognitive competencies necessary in literacy learning. During collaborative pretend play, children participate in sophisticated conversations, practice self regulation through ‘rules of the role,’ and use symbolic and abstract thinking as they pretend and imagine. In addition, children apply analytical thinking as they plan for play, and address and respond to issues that emerge during their play. Oral language, symbolic and abstract thought, analytical thinking, and self regulation are cognitive competencies foundational in early literacy development (Bodrova & Leong, 2010) – all strengthened through children’s ongoing engagement in mature sociodramatic play.

Pretend play mediates learning

Based on the work of researchers like Smilansky, Vygotsky, El’konin, and others, we believe pretend play causes development to happen. Pretend play mediates (i.e. is a go between) a child’s extrinsic experiences and/or perceptions and a child’s internalized understanding. In other words, by engaging in sociodramatic play children come to know and make sense of their world as they act out notions they cannot yet verbally explain. Children act out scenes, dilemmas, or storylines in which they appropriate the required roles by taking the actions on as their own. Within this context, children build capacity to use abstract thought as they imagine, create, and represent ideas (Duncan & Tarulli, 2003).

Children begin thinking in terms of symbols by using objects to stand for something or someone in their play. For example, children might grapple with using a block to represent the role of a dog. Eventually, children come to a point in their thinking that they do not need a concrete item (in this case a block) to represent the dog…they are able think in the abstract, to imagine the role of the dog existing in the play. Scientists like Smilansky, Vygotsky, and El’konin argue that children’s minds change as they engage across time in this level of cognitively demanding pretend play. As children command abstract thought, their minds prepare for comprehending using letter symbols to represent words and ideas. At this point, the symbols D – O – G can begin to make sense as a representation for dog (Bodrova & Leong, 2015; Smilansky & Shefatya,1990).

Pretend play does not just happen

Pretend play may be universal, but it must be intentionally supported in order for preschool children to reach the highest level of sociodramatic play (Leong & Bodrova, 2012). As reflective practitioners in the field of early childhood, we have been provoked to wonder about maximizing and leveraging sociodramatic play possibilities in our preschool classrooms. Specifically, we have asked ourselves deep questions for inquiry:

- What are our own understandings of pretend play?

- How can we plan for pretend play without dictating it?

- Do we recognize when children’s pretend play is ‘stuck’?

- How do we attempt to move the play along without intruding?

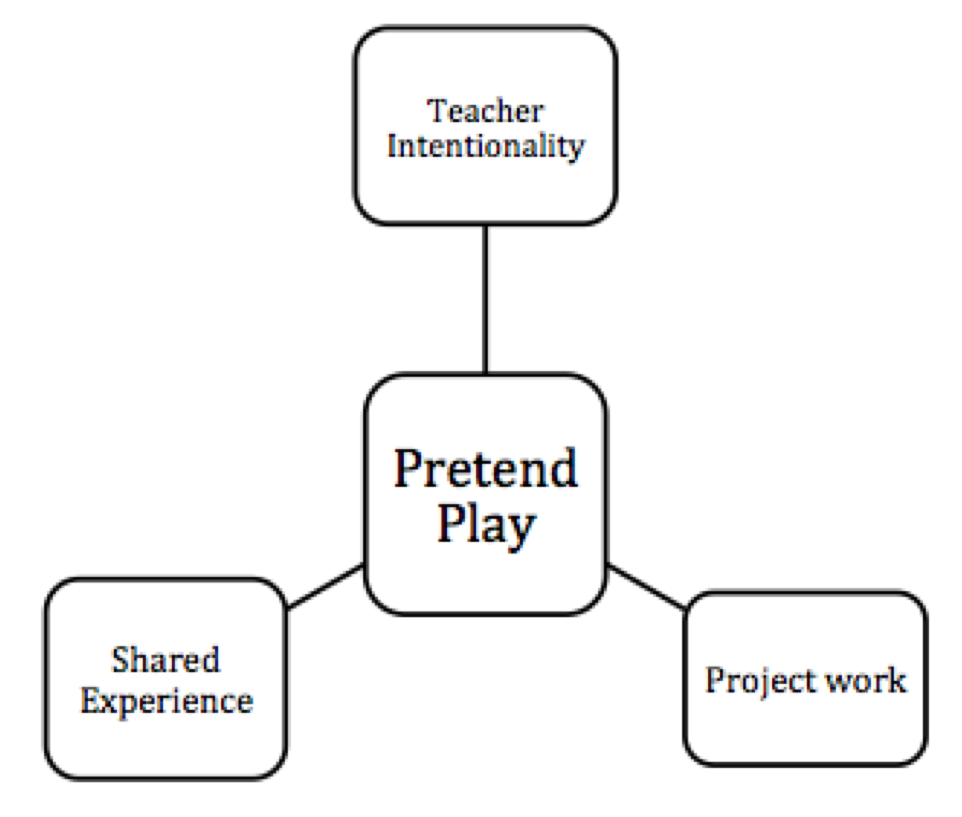

Our questions have led us to revisit the notions of teacher intentionality, shared experiences, and project work for answers.

Supporting mature pretend play through teacher intentionality, shared experiences, & project work

Teacher knowledge leads to teacher intentionality

Just like other developmental domains, pretend play matures across stages. In order to appropriately scaffold children’s play so that it continues to increase in complexity, we recognize we must know more about it. Developed by Deborah Leong and Elena Bodrova (2012), PRoPELS is a tool for identifying ingredients of pretend play, as well as for analyzing specific characteristics of play. PRoPELS is an acronym that stands for six components of pretend play:

P – Plan. Children demonstrate the ability to think about and develop the play before playing occurs. At the highest level of pretend play, the children spend more time planning the play than acting it out.

R – Roles. The children’s roles must fit into the play scenario, and their actions must follow the rules of behavior as determined by the role. In mature play, roles have social relationships and children may play more than one role at a time.

P – Props. A prop can be any real, symbolic, or imaginary object used during play. In the most complex form of play, props are imaginary and are not needed for children to stay in their roles.

E – Extended time frame. This is the duration of the play and its continuation across time, either within one play session, one day, or as indicated in mature play, across several play sessions and days. At this level, play can even be suspended and restarted.

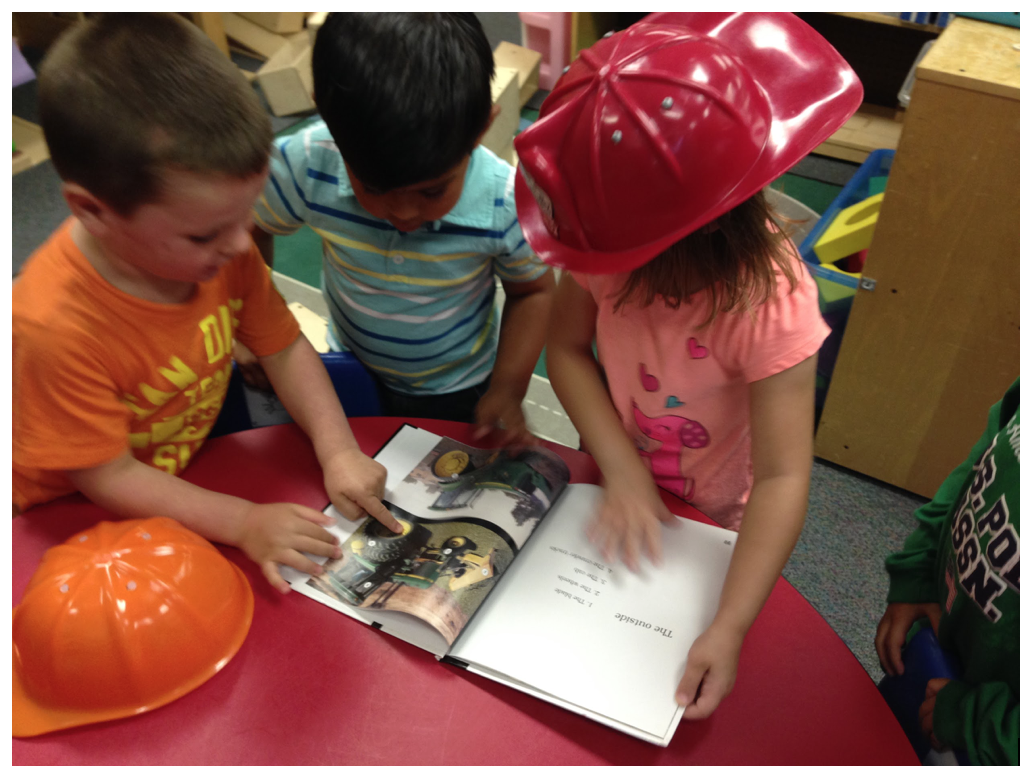

L- Language. Language refers to the words and vocabulary children use to develop a role, scenario, or actions in play. As children mature in their play ability, book language is a part of the role speech.

S – Scenario. The scenario includes the scene and sequence of interactive events that children act out. In mature play, children navigate the unfolding play story in response to previous play or the wishes of the players. Themes from stories and books are used and reenacted (Leong & Bodrova, 2012, p.29).

Shared experiences and project work support the development of pretend play

Next, we looked to shared experiences and project investigations as a vehicle for providing children with context and information to extend pretend play opportunities. We know shared experiences are vital for building a classroom community, so it stands to reason that shared experiences are essential for providing a common framework for children’s staging and engaging in a pretend play scenario. A shared experience can be anything from commonality of everyday life experiences to book reading, time spent together in school, field trips, community events, or project work.

We view project work as an intentional shared experience that can provide children with common experiences and understandings that can enrich sociodramatic play. By definition, project work is “an in-depth investigation of a topic worth learning more about…A research effort deliberately focused on finding answers to questions about a topic posed either by the children, the teacher, or the teacher working with the children“ (Katz & Helm, 1994, p. 1). As preschool children engage in an investigation around a meaningful topic, they gain knowledge to expand their pretend play. Project work experiences broaden the scope of pretend play possibilities, opening the door for children to incorporate new roles, details, vocabulary, materials, facts, or scenarios. Moreover, project work supports pretend play that develops over time. Much like a play scene in pretend play, project work is open ended and emerges through ongoing interactions between children, adults, materials, and ideas.

So, what is the big take a way?

Sociodramatic play is the activity through which young minds grow. Pretend play causes development, and mediates learning within children. Teacher intentionality, shared experiences, and project work can serve to scaffold children’s pretend play and maximize pretend play possibilities. Sociodramatic play is just too important in the learning lives of young children to be left to happenstance.

References

Bodrova, E. & Leong, D. (2015). Vygotskian and post-vygotskian views on children’s play. American Journal of Play, v.7, n.3, p.371-388. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1070266.pdf

Leong, D. & Bodrova, E. (2012). Assessing and scaffolding: Make believe play. Young Children, v67 n1 p28-34. Retrieved from www.researchgate.net/publication/292513144_Assessing_and_scaffolding_make-believe_play

Bodrova, E., Leong, D., Davidson, F. W., Davidson, J. M., Vygotskiĭ, L. S., & Davidson Films. (1995). Play: A Vygotskian approach. Davis, CA: Davidson Films.

Duncan, R. & Tarulli, D. (2003). Play as the leading activity of the preschool: Insights from Vygotsky, Leont’ev, Bakhtin. Journal of Early Education and Development v.14. (n.3). p 271 -289.

Early Childhood Learning Knowledge Centre. (2006). Let the children play: Nature’s answer to early learning. Retrieved from http://galileo.org/earlylearning/articles/let-the-children-play-hewes.pdf

Helm, J. H. & Katz, L. G. (2010). Young investigators: The project approach in the early years. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Smilansky, S., & Shefatya, L. (1990). Facilitating play: A medium for promoting cognitive, socio-emotional, and academic development in young children. Gaithersburg, MD: Psychological & Educational Publications.