Written by:

Robyn Brookshire PhD., Director, UT Early Learning Center for Research and Practice

Alex Morgan, Community Outreach Specialist, Boulder Journey School

Kathryn Humber MS., Demonstration Teacher, UT Early Learning Center for Research and Practice

Frances and David Hawkins, educational philosophers, drew upon their respective experiences in classrooms and the field of physics with influences from contemporary social-constructivist educators, to develop their philosophy of education that speaks to the value of experiential learning. The work of Frances and David Hawkins continues to be relevant to contemporary early childhood teachers seeking to implement inquiry-based, meaningful project work with a wide range of ages. This piece highlights the Hawkins’ theoretical cycle of “Messing About” (Hawkins, 1974) with materials and ideas as a framework for guiding children’s and adults’ inquiry. Examples from classrooms at the University of Tennessee Early Learning Center and Boulder Journey School are provided to illustrate innovative applications of this cycle and the ways teachers form relationships utilizing the Hawkins’ approach in order to deepen their understanding of how children express and pursue questions about the world around them.

Frances and David Hawkins, educational philosophers, drew upon their respective experiences in classrooms and the field of physics with influences from contemporary social-constructivist educators, to develop their philosophy of education that speaks to the value of experiential learning. The work of Frances and David Hawkins continues to be relevant to contemporary early childhood teachers seeking to implement inquiry-based, meaningful project work with a wide range of ages. This piece highlights the Hawkins’ theoretical cycle of “Messing About” (Hawkins, 1974) with materials and ideas as a framework for guiding children’s and adults’ inquiry. Examples from classrooms at the University of Tennessee Early Learning Center and Boulder Journey School are provided to illustrate innovative applications of this cycle and the ways teachers form relationships utilizing the Hawkins’ approach in order to deepen their understanding of how children express and pursue questions about the world around them.

Introduction of the Hawkins’ work

With David’s background in physics, he worked as the historian on the Manhattan Project, which was the project responsible for the creation of the atomic bomb. After completing work on this project, David felt a deep concern for the direction society was taking. As was their custom, Frances and David collaborated , drawing on Frances’ work with children, and together they developed their philosophy of education – one which places a strong emphasis on the roles of time and space for exploration and building meaning.

The Hawkins’ philosophy recognizes the responsibility of fostering this kind of thinking and learning as a means to support the continuation of approaching the world with a questioning attitude of rather than an assumptive attitude. This questioning attitude, that children often adopt naturally, has a tendency to be lost in adulthood. Frances and David valued supporting adults in maintaining this approach to learning in themselves so that they could then support children in the same way.

The Mountain View Center for Environmental Education, founded by Frances and David Hawkins in Boulder in the mid-1970s was one strategy they used for supporting adults in continuing to cultivate their own paths of inquiry-based learning. They regularly offered workshops for teachers on topics ranging from basket-weaving to block balancing to bubble blowing. The goal of these workshops was not necessarily for teachers to take the content back to their classrooms. Instead, it was for teachers to have the visceral sensation of learning through “messing about”.

What is “Messing About”?

Most early childhood educators will tell you that the ways children explore materials are not only important windows into their learning, but also that the particular ways children engage and form relationships with materials is worthy of close study. “Messing About” provides a way to conceptualize, understand, observe, and interpret children’s work as they explore materials. David Hawkins proposed this as a cyclical system to guide teachers’ understandings after spending time observing young children’s explorations with science materials (Hawkins, 2002).

The Messing About cycle consists of three phases, with each phase noted by shapes ( ⚫, ⬛, ▲) rather than alphabetically or numerically, so as to imply that they can take place in any order. A crucial component in Messing About is ensuring that both time and space need to exist for the learner to move through all three phases.

| Phase ⚫ a time for unstructured, open-ended play while teachers observe the children’s work | Phase ▲: a time for differentiating work by identifying and pursuing multiple possibilities based on observations | Phase ⬛: a time for unpacking and verbalizing theories that have developed, through discussion among children and teachers |

Hawkins Centers of Learning, n.d.

The phases of learning can be cycled through on a micro-level, in which we examine the ways the individual moves through all three phases in one short-term experience; or on a macro-level, in which we examine the ways the individual or group shifts from phase to phase over a longer period of time (e.g., infants spend much of their time in explorative work (⬤ phase) while older children spend more energy developing goals (▲ phase) and reflecting on their work (⬛ phase)).

Incorporating Hawkins influences with documentation

The following project shows an example of the influence of the Hawkins’ work at the University of Tennessee Early Learning Center for Research and Practice, where the approach to curriculum relies on inquiry-based project work with children. One of the trickiest parts of guiding project work with children lies in the decisions teachers must make about when to bolster, extend, pause, or reinforce children’s explorations with materials. Using both the Hawkins’ lens to watch children messing about in combination with supportive documentation approaches can be instrumental for teachers’ roles as facilitators of project-based inquiry. At the University of Tennessee Early Learning Center, we have been revisiting the Hawkins’ work for several years and, more recently, a few teachers added a form of documentation called the Floorbook Approach (Warden, 2017). Applying the phases of messing about to observations and documentation of children’s work gave our teachers a solid point of reference; a thinking tool so they could analyze what they see children doing and can then ask themselves questions such as: What are the children asking of the materials? What problems are the children encountering and trying to solve with these materials? Are the children still exploring, or are they moving into the ▲ and ⬛ phases where they are testing out different possibilities or developing theories about what could happen next if they make changes? Using the Hawkins’ work as a lens allowed our teachers to make sense of the complexity of children’s work and to narrow in on the questions children are asking. This, in turn, provoked the teachers to consider the next possible steps and invitations they might provide to the children. As a community of practice, we appreciated that finding ways to support children moving from the ⬤ phase to the ▲ and ⬛ phases was very complex. In combination with influence from Reggio practices (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 2012), teachers can consider ways to help the children revisit and re-encounter their previous questions about the materials so they can stay involved with particular questions and pursue them with more depth.

The following project shows an example of the influence of the Hawkins’ work at the University of Tennessee Early Learning Center for Research and Practice, where the approach to curriculum relies on inquiry-based project work with children. One of the trickiest parts of guiding project work with children lies in the decisions teachers must make about when to bolster, extend, pause, or reinforce children’s explorations with materials. Using both the Hawkins’ lens to watch children messing about in combination with supportive documentation approaches can be instrumental for teachers’ roles as facilitators of project-based inquiry. At the University of Tennessee Early Learning Center, we have been revisiting the Hawkins’ work for several years and, more recently, a few teachers added a form of documentation called the Floorbook Approach (Warden, 2017). Applying the phases of messing about to observations and documentation of children’s work gave our teachers a solid point of reference; a thinking tool so they could analyze what they see children doing and can then ask themselves questions such as: What are the children asking of the materials? What problems are the children encountering and trying to solve with these materials? Are the children still exploring, or are they moving into the ▲ and ⬛ phases where they are testing out different possibilities or developing theories about what could happen next if they make changes? Using the Hawkins’ work as a lens allowed our teachers to make sense of the complexity of children’s work and to narrow in on the questions children are asking. This, in turn, provoked the teachers to consider the next possible steps and invitations they might provide to the children. As a community of practice, we appreciated that finding ways to support children moving from the ⬤ phase to the ▲ and ⬛ phases was very complex. In combination with influence from Reggio practices (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 2012), teachers can consider ways to help the children revisit and re-encounter their previous questions about the materials so they can stay involved with particular questions and pursue them with more depth.

Pathways versus ramps, and what is an incline?

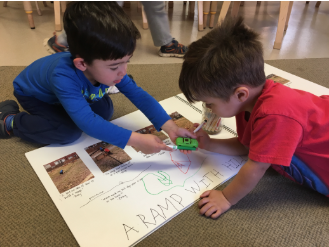

At the beginning of a year-long ramp study, two teachers, Kathryn and Dilyn from the University of Tennessee Early Learning Center, began incorporating different ramp-building materials in their preschool classroom. They initially chose to allow the children an extended amount of time exploring the different ramp-building materials (⬤ phase); however, as the children spent time exploring the different materials, the teachers chose to closely observe and document the actions the children were making. At the same time, as part of ongoing teacher development and coaching, the teaching team was revisiting David Hawkins’ chapter on Messing About (Hawkins, 2002). This time, revisiting the work on Messing About helped the teachers consider the different stages of exploration that the children moved through as they explored the concept of “What is a ramp?”. Using the floorbook to document and reflect, they began to notice children moving into the ▲ phase as children began to build more and more ramps. As the children constructed their versions of ramps, the teachers noticed that they were often flat on the ground. As the children tried to roll balls along these horizontal paths, they didn’t see the balls gain momentum unless someone pushed the ball along the pathway.

Noticing this dialogue between the children and their materials, the teachers made a choice to pause on this dilemma to help the children unpack and explore their understanding of how the materials, their structural designs, and gravity worked together as a system.

After reviewing a series of documentation of children working in the ⬤ and ▲ phases, Robyn, as the pedagogical coach with Kathryn and Dilyn, suggested that it might be valuable to ask the children to consider whether a flat pathway is the same as a ramp and, to further children’s understanding, that they introduce the concept of inclines and angles to the children. Kathryn created a physical provocation that she introduced during a whole group meeting which would allow the children to experiment with releasing one wooden ball on a ramp piece that was placed flat on the ground and releasing another wooden ball on the ramp that was placed on a few blocks, therefore creating an incline with the ramp piece. The children and teachers took time to closely observe the actions of the ball at the two different angles and then discussed some of the things that they noticed. Several comments from our discussion led the children to make several clear observations about the differences between ramps and pathways, which encouraged the children to begin explaining their thinking in greater detail (⬛). We added them to the Ramps Floorbook as a way to remember and review their thoughts throughout this extended project work.

“We had an experiment. We wanted to see which ball would roll. The ball on the flat road didn’t roll. The flat road is not a ramp, the one with the slope is a ramp!” -GHB

“I had to use force to make the ball move on the track that was fast. It wouldn’t roll on it’s own!” -GG

“The road with no incline made the ball stay still. The ball on the incline rolled!” -LJ

The decision about when to introduce a concept or when to add a provocation to  children’s inquiry can feel like a very tricky pedagogical knot. Kathryn and Dilyn were very sensitive to children’s ownership of their processes and did not want to redirect children’s lines of inquiry. Reading David Hawkins’ work, however, gave the teachers opportunities to interpret the shifts between the phases of work and to feel more confident about knowing when and how to extend children’s inquiry into new conceptual understandings. Introducing new provocations led the children down a path of discovery with ramps that lasted many weeks, as the children continued to cycle through all three phases while tinkering and testing theories with the different angles, balls, and materials. All the while, Dilyn and Kathryn invited the children, through the use of the floorbook, to revisit and re-engage with their theories and tests:

children’s inquiry can feel like a very tricky pedagogical knot. Kathryn and Dilyn were very sensitive to children’s ownership of their processes and did not want to redirect children’s lines of inquiry. Reading David Hawkins’ work, however, gave the teachers opportunities to interpret the shifts between the phases of work and to feel more confident about knowing when and how to extend children’s inquiry into new conceptual understandings. Introducing new provocations led the children down a path of discovery with ramps that lasted many weeks, as the children continued to cycle through all three phases while tinkering and testing theories with the different angles, balls, and materials. All the while, Dilyn and Kathryn invited the children, through the use of the floorbook, to revisit and re-engage with their theories and tests:

“The floorbook has kept the focus and interest in ramps current because we are constantly revisiting their work. When we allow children to engage in the reflective process with us they begin to deepen their knowledge and understanding of how their work relates the world around them. The children have been given the time to explore the answers to their questions in depth. This opportunity to have rich understanding of a material has encouraged the children to explore all of the curricular areas while investigating ramps. They have spent time writing, drawing, counting, measuring, engaging in dialogue with others, researching information, and strengthening countless other skills. They are blending new knowledge with prior knowledge and creating an understanding of it all.” -Kathryn

Interpretation and Documentation in Multiple Age-Levels

To examine the phases of the Messing About cycle on a macro level, let us look to a school-wide examination of the intersections between digital and analog possibilities at the Boulder Journey School. In our early stages of exploring this topic as a school, we existed, both teachers and children, in a strong state of the ⬤ phase. Within this overarching phase of exploration, we moved through all the phases many times.

One path we played with was the invitation for children to interact with cardboard boxes that acted as projection screens for digital videos. A video of Diggum, our school’s beloved pet fish, was shone into a large appliance box.

For the infants who entered this space, there was a palpable sense of wonder and curiosity as they examined the newly developed landscape. This space to explore provoked questions from the infants. Their gazes, their movements into and out of the box, and the ways they reached with their hands to try to grasp the giant fish, demonstrated the range of questions they were asking from ‘what am I encountering’ to ‘how is this happening’. The teachers observed the infants interactions with the projection and took notes on these observable actions. In this way, the infants’ time in the ⬤ phase offered a background of information for both the infants and the teachers. To the infants, these experiences acted as a way to develop, as Hawkins called it, an “acquaintance with the sheer phenomena” of digital  projection (2002, p. 69). They developed familiarity which could, in time, grow into understandings about the language of physics, the language of light, the language of digital experiences. To the teachers, these experiences acted as a form of crucial feedback about the children, their interaction styles, and their curiosities. From these ⬤ phase explorations, the teachers found ways to support the shift into the ▲ and ⬛ phases.

projection (2002, p. 69). They developed familiarity which could, in time, grow into understandings about the language of physics, the language of light, the language of digital experiences. To the teachers, these experiences acted as a form of crucial feedback about the children, their interaction styles, and their curiosities. From these ⬤ phase explorations, the teachers found ways to support the shift into the ▲ and ⬛ phases.

This same invitation was offered to classes of toddlers as well. While we certainly observed the toddlers engaging in an exploratory manner (⬤), we also observed them a strong sense of them defining a pathway for their explorations (▲).

Some of the toddlers engaged with the space as a backdrop for clear dramatic play scripts as they became aquatic creatures who swam beside Diggum. Other groups of toddlers formulated questions about the mechanics of the invitation itself.

Some of the toddlers engaged with the space as a backdrop for clear dramatic play scripts as they became aquatic creatures who swam beside Diggum. Other groups of toddlers formulated questions about the mechanics of the invitation itself.

We observed Wyatt and Bailey, both age 2.5, playing inside the box for a time. At one point, Bailey sat inside of the box and noted with dismay that he could not see the projection when he faced out (towards the projector).

He turned to his teacher, Caitlin, and proclaimed, “It’s not going!”

Caitlin: “It’s in there. When you’re in, it’s on your face. See! It’s on Wyatt.”

Bailey: “It’s on Wyatt!”

Wyatt: “It’s on me! There’s Diggum! (moves in to the box) Now I’m behind Diggum. (moves out of the box) Now I’m not behind Diggum.”

While Bailey and Wyatt had identified a path for exploration (▲), that of gaining a deeper intimacy with the physics of light and shadow, they also stepped into the ⬛ phase as they developed theories of why the Diggum moved from being on them to behind them. And, of course, they spent time in the ⬤ as they played with these ideas.

Hawkins noted that through these phases, “discoveries were made, noted, lost, and made again…. When the mind is evolving the abstractions which will lead to physical comprehension, all of us must cross the line between ignorance and insight many times before we truly understand” (Hawkins, 2002, p. 70).

Let us take one more peek at how Diggum and his box facilitated the shifts between the three phases, this time with a group of 3- and 4-year-old children. They were in a macro ⬛ phase with storytelling; an exploration in which their class had been engaged for many months. They were uncovering new understandings about both the mechanics and the emotional output of storytelling.

This group of children had developed a ritual of offering each other birthday gifts in the form of stories composed with words that started with the same letter as the birthday child’s. They had discussed extending this ritual to offer gifts to community members beyond the walls of their classroom – one of whom was Diggum. To support this ▲ thread, their teacher invited them to encounter Diggum in the box.

Adult work with Messing About

“If teachers can join us in mapping paths into subject matter, they are on their way to being able to do so for children.” – (Hawkins, 2002, p. 54)

“If teachers can join us in mapping paths into subject matter, they are on their way to being able to do so for children.” – (Hawkins, 2002, p. 54)

A big question in this delicate dance remains: how do we know how to facilitate the shift between the phases? How do we know when to engage in, as Frances referred to the process, “stepping in and step out” of the children’s work? (Hawkins, 1974)

Looking to the Mountain View Center as inspiration, we can prioritize finding time for teachers to engage in the three phases of messing about themselves. When teachers get their hands on materials, not only do they develop a deeper understanding of the affordances and shortcomings of the material, they also develop a strong sense of empathy for the ways children shift between the phases.

Both University of Tennessee Early Learning Center and Boulder Journey School  engage in regular offerings of materials workshops for educators, both for their faculty and the larger community as a whole. During these workshops, it is blazingly clear how strongly adults differentiate their play as children do. Some adults enter the play with a tendency to touch every material put out. What do the materials say to me? How do they respond to my touch? What dialogue can I enter with them? These adults are entering in a ⬤ phase, with a strong desire to uncover possibilities and no superimposed goal.

engage in regular offerings of materials workshops for educators, both for their faculty and the larger community as a whole. During these workshops, it is blazingly clear how strongly adults differentiate their play as children do. Some adults enter the play with a tendency to touch every material put out. What do the materials say to me? How do they respond to my touch? What dialogue can I enter with them? These adults are entering in a ⬤ phase, with a strong desire to uncover possibilities and no superimposed goal.

Some adults, when asked to play immediately turn to a neighbor to discuss the provocation. What is this asking me to do? What will I gain from this? How will I build new understandings? These adults are entering through a ⬛ phase, seeking to understand the complexities of the work they are about to engage in. What theoretical framework can guide their play?

Some adults select what materials they will use before the play time has even begun; beginning the work with their intentions and desires. Through their play, they may go through a series of iterations and prototypes, all the while guided by this ▲ phase of exploration.

Some adults select what materials they will use before the play time has even begun; beginning the work with their intentions and desires. Through their play, they may go through a series of iterations and prototypes, all the while guided by this ▲ phase of exploration.

When the adults are called to reflect on their experiences, again and again, this notion of empathy arises. They share that they can feel why one child might choose work in the same space for multiple days in a row: perhaps they are focused in the ▲ phase and not yet ready to shift. They also express an understanding for why a child might take longer to settle into the routine of the day: perhaps they are starting in a ⬤ phase and using that extra time to sample the offerings the day might bring.

This experience of teachers moving through the phases themselves offers an understanding of the value of an appropriate amount of time and space as well how to support children in utilizing that time to go deeper in their explorations.

Application to Diverse Contexts

We have developed a lists of considerations/questions to ask when planning for applications of Messing About with all ages in different contexts. We invite you to get in touch with us the ways you view how this work can respond to the strengths and opportunities in your specific settings. As pedagogical leaders, we too are often on a journey of messing about with our practices in designing learning environments and systems for both adults and children. We thrive on dialogue that is created when new and divergent ideas, theories, and experiences consider:

- What materials have open-ended possibilities (think “loose parts”, natural materials, recycled materials, tools).

- What materials offer complexity and sophistication to the work. How do we offer materials in a way that the complexity is increased?

- What materials have particular meaning to the social and natural ecology of your own program. Are there aspects of community that can be woven into the materials or lines of inquiry (e.g., geographical settings)?

- Who we can invite into the work of Messing About as we engaged in this work with children. Can we create shared experiences with families, community experts, and pockets of the community who also have a vested interest in similar questions the children are asking?

- When working within time constraints of pre-existing schedules, – how can children’s work be saved for revisiting? Can photographs offer the possibility to revisit?

For further reading:

Hawkins Centers of Learning Website

University of Tennessee Early Learning Website

Boulder Journey School Website

How to Reach Us:

Robyn Brookshire – rbrooks8@utk.edu

Alex Morgan – alex.morgan@boulderjourneyschool.com

Kathryn Humber – kbarr@utk.edu